What does “centralisation” and “decentralisation” really mean?

The debate between “centralisation” and “decentralisation” is often framed as a binary choice, but this perspective completely misses the point. Advocating for a decentralised foundation (aka a decentralised base layer)— whether in the economy or social media — does not imply that the entire system should be decentralised from the ground up to be fair or functional.

In fact, the idea of a decentralised foundation does not, by any stretch of the imagination, suggest an environment free from any form of centralisation. Rather, it is essential to recognise the role of a decentralised base layer while understanding that centralisation more efficiently solves many complexities in higher layers.

Centralisation refers to the concentration of control, authority, and decision-making power within a single or a few entities, which creates a “single point of failure.” In contrast, decentralisation disperses power, control, and decision-making across various entities, ensuring there is no single point of failure.Consider the analogy of constructing a building: you would want a solid, immovable, and incorruptible foundation (decentralised) to support the structure, but the building itself (1st layer of centralisation) can house various companies and services (2nd layer of centralisation) that operate above this foundational framework. Over-centralising the entire structure would lead to structural biases, just as a completely decentralised building would lack the coordination and streamlined operations provided by centralised companies. A decentralised base layer does not mean anarchy or the absence of rules; rather, it describes a structure in which the rules are transparent and incorruptible, allowing centralised entities built on top to operate — or compete — on a level playing field.

Natural Laws

Before we delve into human-made examples, let’s consider the natural laws that every organism on Earth must abide by — namely, the natural laws, like gravity and the cycles of day and night. These laws form a decentralised base layer upon which all living organisms act. In the savanna of East Africa, no one can escape the pull of gravity or the relentless rays of the sun. Within this environment — or atop the base layer of natural laws — we find numerous centralised entities. A family of elephants, for instance, is often led by a matriarch who dictates the rules for the group, just as an alpha male lion does for its pride. It’s natural for animals — just as it is for humans — to form centralised entities. This isn’t a coincidence or something created by force, but rather a result of evolution that has proven necessary for survival, as the group can act more efficiently than any individual alone. This is yet another example of how centralisation in the upper layers, supported by a decentralised foundation, works together to create a balanced and efficient system. Centralising the base layer, in this analogy, would be like giving one group of animals the ability to change the weather — something that would undoubtedly spell the end of the ecosystem.

Here are some human-made systems, based on open protocols, that function as decentralised base layers:

Mathematics

Mathematics serves as a perfect example of a decentralised open protocol, characterised by its universally acknowledged, unalterable principles that form the backbone of our understanding of the universe. These principles are transparent, universally accessible, and fixed, with no single central authority able to modify them.

Centralised entities, such as academic institutions and communities of mathematicians, play an essential role, constructed upon this decentralised foundation, to advance the field. Although these institutions centralise education and foster discussions, they lack the power to change the fundamental mathematical rules to fit their own preferences or agendas. They can propose new theories or interpretations; however, these ideas must withstand stringent scrutiny and be accepted based on the pre-existing mathematical laws. For example, if a mathematician claims to have solved a complex equation related to quantum physics, the wider mathematical community can independently verify this claim by applying the relevant mathematical principles. This process of peer verification highlights the decentralised nature of mathematical knowledge, demonstrating that while learning and debate may be organised by centralised bodies, the core principles of mathematics remain a pure, decentralised protocol that no single entity controls.

Internet

The Internet is yet another example of a decentralised base layer of communication, maintained not by any single entity but by a collective of global participants. At the foundational level, the Internet’s physical infrastructure, consisting of servers, cables, and satellites, is distributed across the globe and owned by various entities, from private individuals to international corporations and governments. This diversification in ownership helps ensure that no single point of failure can entirely disrupt the network.

While a government might block citizens from accessing certain websites through Internet service providers, they cannot erase information from the fundamental infrastructure of the Internet.Built upon this base layer, various services and platforms operate as centralised entities. While individual services can be regulated or restricted, the underlying protocols remain free and open for innovation by anyone. Centralised entities, such as tech giants like Google or nation-states, might take their websites offline or attempt to block access and censor certain content within these centralised layers, but they cannot manipulate the base layer itself. For example, while a government might block citizens from accessing certain websites through Internet service providers, they cannot erase a website from the fundamental infrastructure of the Internet. This structure underscores the decentralised nature of the Internet, where the foundational layers remain resilient and outside the control of any single centralised authority, ensuring the flow of information remains as unrestricted as possible.

Here are some examples of current systems built on centralised base layers that have decentralised base layer alternatives:

Social Media

Platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok are centrally controlled from the ground up. This means that the base layer — the infrastructure, the data, and the user relationships — are owned and managed by a single entity. These platforms have the power to change rules and algorithms and even remove content or ban users at their discretion. For example, if you post content that violates their policies, your account can be suspended or deleted, resulting in the loss of your followers, posts, and overall online presence on that platform.

In contrast, Nostr is a censorship-resistant open protocol that empowers users to connect, share, and post without being subject to the control of a single entity. Unlike a social media platform, Nostr serves as a decentralised base layer that supports user connections and facilitates the development of centralised applications like Damus or Primal, which are built on top of it. Although these centralised applications can run their own algorithms and impose restrictions, users can easily migrate to another application within the Nostr network, should they want to, without losing their data, followers, or posts. This flexibility is possible because user data and relationships are not tied to any specific application but exist independently across the decentralised Nostr network.

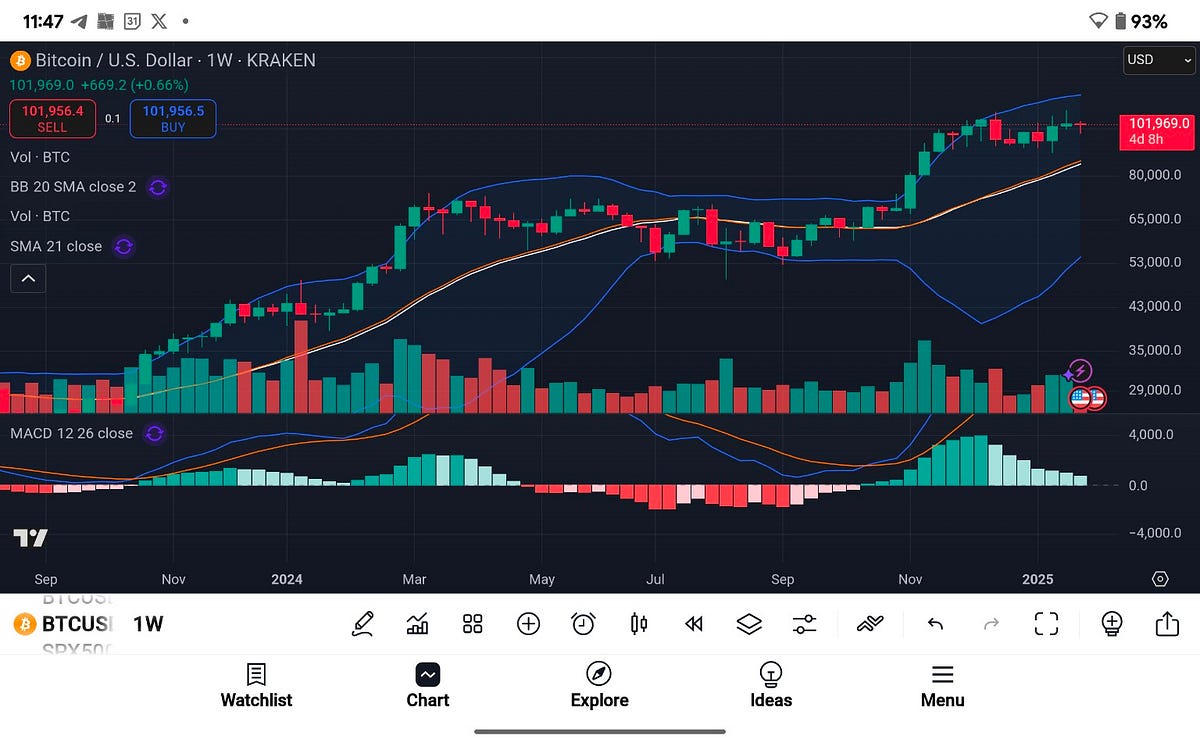

The Economy

FIAT money, the dominant monetary system currently adopted globally, is government-backed. This structure means that the world economy operates with a centralised base layer, prominently led by the United States, which holds the position of the global reserve currency.

Historically, before 1971 and at several points prior, money was often backed by commodities like gold or silver. During these periods, the monetary system exhibited characteristics of a decentralised base layer, as no single entity possessed the power or capability to manipulate the entire system unilaterally. However, forms of sound money — such as those pegged to gold — have historically faced challenges. Gold, being impractical for everyday transactions, required centralised storage in banks, which eventually led to manipulation by these institutions or governments.

The economy and money function as the lifeblood of human interactions and cooperation. This makes it particularly dangerous when that system has a single point of failure that can be manipulated by a small minority. While natural laws serve as our ultimate foundation, the economy can be considered the foundational layer of human interaction, upon which everything else is built upon, including the internet, social media, and university education.

Corrupting money allows for indirect control over human behavior, shifting it to benefit the manipulator.

Bitcoin, in contrast, operates on an open protocol, akin to mathematics or the internet, with a decentralised base layer. This means that no single entity has the power or ability to change the fundamental rules of the protocol. The point of adopting Bitcoin as a form of money is not to eliminate centralisation in higher layers, such as those involving companies or governments. Instead, it ensures that all parties adhere to the same immutable rules. This structure fosters a fairer and more stable economic foundation by preventing changes to the monetary system. By grounding the system in a decentralisation base layer, it closes the door to corruption, manipulation, and unchecked power that often accompany centralised control. In such a system, the only way to earn money — since the system cannot be manipulated in one’s favor — is by creating something of value to others and exchanging it for money.

The Key Distinguisher: The Base Layer

Understanding the nature of a system’s base layer is crucial in predicting its long-term viability and integrity. When the base layer is centralised — possessing a single point of failure — it inevitably opens the door to potential manipulation and corruption. This vulnerability means that over sufficient iterations, any centralised base layer will become corrupted as there will be enormous economic incentives to yield that power.

Centralisation at the base layer implies that everything built upon it is, in a sense, enslaved to or at the mercy of the controlling entity. This dependency creates problematic and often destructive power dynamics. For example, in the realm of centralised social media platforms, users become increasingly loyal as their followings grow, making them more susceptible to the platform’s evolving rules. Deviating from these rules can result in the banning of the user without warning, and severing ties with the platform over disagreements with new policies will likely lead to the loss of historic messages and followers, potentially causing significant financial losses.

This scenario is particularly perilous given the current monetisation strategies of social media, which primarily depend on advertising revenue, coupled with the FIAT monetary system that favours short-termism over long-termism. Advertisers, the main revenue source, are fundamentally seeking engagement, which incentives platforms to create algorithms that foster division and controversy. As a result, social media platforms are compelled to cater to corporate advertisers and, to some extent, government regulations that can jeopardise their operations. This dynamic highlights how platforms are not neutral venues for discourse but are instead driven by financial incentives that may conflict with the well-being or preferences of their users.

Contrast this with a decentralised alternative, such as that proposed by protocols like Nostr. In such environments, while the platforms built on top of the base layer may still operate as centralised entities with their own algorithms and advertising models, they ultimately remain accountable to their users. If users disagree with a platform’s policies, algorithmic choices, or monetisation choices, they can migrate seamlessly to another platform without losing their network or followers. This flexibility significantly empowers users, ensuring that platforms must continually earn their users’ trust and participation, rather than coercing it through monopolistic control.

For a deeper exploration of how government and decentralisation interact, be sure to check out my follow-up article, “Killing the Myth: Government vs Decentralisation.” This piece builds on the concepts discussed here, offering further insights into the often misunderstood relationship between decentralisation and the government.

Centralisation vs Decentralisation: Crafting a Coherent Understanding was originally published in The Capital on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

2 months ago

44

2 months ago

44

English (US) ·

English (US) ·