Rethinking Inflation: Understanding Inflation as a Vector, Not a Number

Price inflation in the broader economy, influenced by both monetary inflation and various supply and demand dynamics, is a complex phenomenon that cannot be adequately captured by simplistic metrics like the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or other standard inflation indexes alone.

Before we continue, let’s clarify two terms:

Price inflation refers to the general increase in the prices of goods and services across an economy over time, which reduces the purchasing power of money. It’s the phenomenon where you need more money to buy the same amount of goods or services as before.

Monetary inflation, on the other hand, specifically refers to the increase in the money supply within an economy. This influx of money inevitably inflates prices in a direct proportion to the money expansion, either by directly raise prices or, at the very least, prevent them from falling. While the government would like you to think that price inflation is synonymous with the CPI, this is a misconception that we will dispel shortly.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) focuses on a specific basket of mostly manufactured goods and services that a typical consumer might use, such as food, clothing, housing, and transportation. While this provides a snapshot of price changes for these items, technological advancements, and efficiencies generally hold down their price increases by expanding supply.

However, this is not the case for scarce, desirable goods such as real estate. Unlike mass-produced consumer goods, these fixed-supply assets cannot be easily or readily increased to meet rising demand. Therefore, it is more accurate to compare inflation to those assets.

To better understand true inflation, it is crucial to recognise the dynamics of individual goals and ambitions. For example, while the CPI might show a moderate inflation rate, the cost of city housing in most major cities, such as Stockholm — where supply is geographically fixed — has increased by about 7% annually over the last 100 years. Similarly, the S&P 500, representing a scarce basket of the top 500 largest US companies, has had an annual growth rate of about 10% over the same period. When subtracting the annual real productivity growth rate of 2–3%, which reflects improvements in efficiency per unit, the annual growth arrives at about the same figure, ~ 7%. Notably, this is the same annual growth rate at which the broad money supply has also been growing over the same period.

The argument here is that the price increases in these fixed-supply assets, such as real estate in major cities, are not due to the appreciation of the intrinsic value of the assets themselves but rather are driven by inflationary pressures from an expanding money supply.

While price inflation of consumer goods, such as those captured with CPI, have “only” experienced an annual price inflation rate of about 3% over the last 100 years, the price inflation of scarce and desirable assets — which is a much more accurate baseline for the average economic participant’s ability to generate wealth and improve their standard of living over time — has increased more in line with the broad money supply growth.

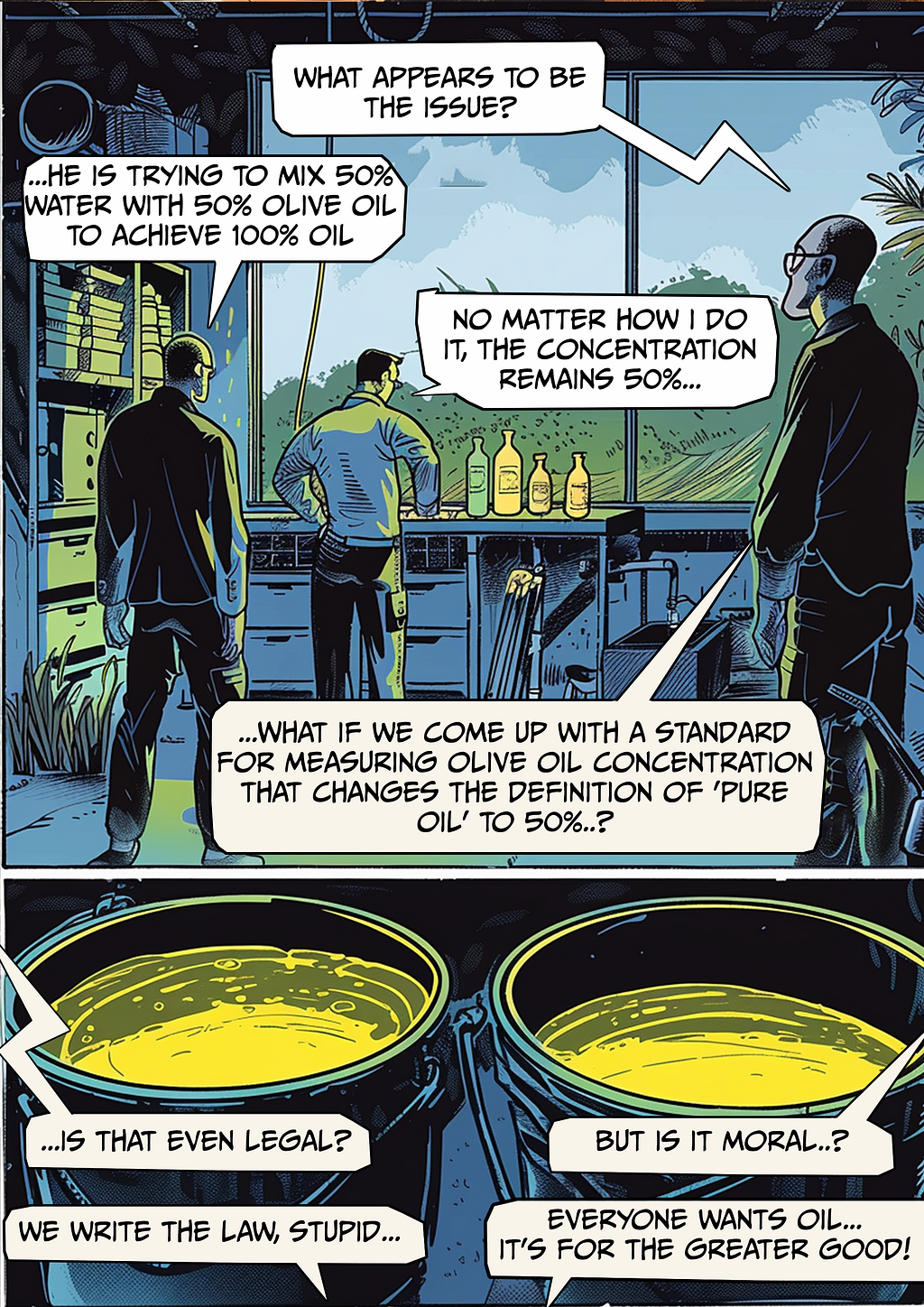

No matter how you mix 1 litre of oil with 1 litre of water — whether you pour the oil into the water or vice versa — you will always end up with 50% oil and 50% water.The point is that when choosing a measurement of inflation to rely on, ask yourself:

Do I accept the government’s aspirations for me — which likely do not include ever owning a home — or do I consider what is reasonable to aspire to in my life and choose a measurement based on that?

When you ask yourself that question, you will begin to realise that inflation is a vector. If your goal is to build something of value over your lifetime and leave more for your children than you inherited, you will find that the CPI inflation rate is extremely conservative. The actual inflation rate aligns more closely with the broad money supply growth. This, of course, is no coincidence. No matter how you mix 1 litre of oil with 1 litre of water — whether you pour the oil into the water or vice versa — you will always end up with 50% oil and 50% water. Similarly, increasing the money supply by 7% a year will have an inflationary effect of 7%.

Ultimately, regardless of what measure we use, an economy based on the founding principle of chronic inflation and constant money supply growth inevitably leads to a total erosion of purchasing power — it’s just a matter of whether it happens sooner or later. The more natural state of an economy, as you will find through my writing, is deflationary, where purchasing power is at worst maintained over time and more likely to appreciate as efficiency improves in the overall market — which it does over the long-term as we accumulate knowledge faster than we lose it.

The true light bulb moment occurs when you understand this concept. Consider something from the basket of goods that the CPI measures, such as the price of bananas. If banana prices have only increased by 3% annually over the past 10 years while the money supply has been expanding by 7%, where did the nominal 4% go? The answer is that those producing bananas have become 4% more efficient in bringing them to market. Therefore, without the money supply growth, bananas should have been 4% cheaper each year.

The graph below illustrates the relationship between the broad money supply (M2) in Sweden, price inflation of housing, various price inflation indexes, and median salaries over the past 30 years. The dotted blue line represents the growth of the money supply, averaging around 6–7% annually during this period.

While it can be argued that living standards have been improved, as indicated by the comparison between median salaries (orange) and the Consumer Price Index (green), the increase is only marginal, and I’d beg to differ. Over the same timeframe, housing prices in Stockholm — a market with a geographically fixed supply — have more than sevenfold, while median salaries have only slightly more than doubled.

Housing overall in Sweden has more than quadrupled in price, which means that compared to 1996, it’s more than twice as hard to buy a house today compared to then.

If one uses the CPI as the sole measure of price inflation, an important detail is overlooked: for those intending to ever own a home, it becomes exponentially more difficult to enter the housing market with each passing year.

None of this is, of course, a coincidence or surprising — and won’t stop anytime soon — it can’t stop any time soon — as a debt-driven economy must continue printing money to service its ever-increasing levels of debt. When the money supply expands by 7% annually, it’s only natural that scarce and desirable assets, like geographically fixed housing, increase in price by the full 7% plus any additional demand. Meanwhile, goods whose supply can be expanded resist these price increases, often rising less, when, in reality, they should have decreased in price.

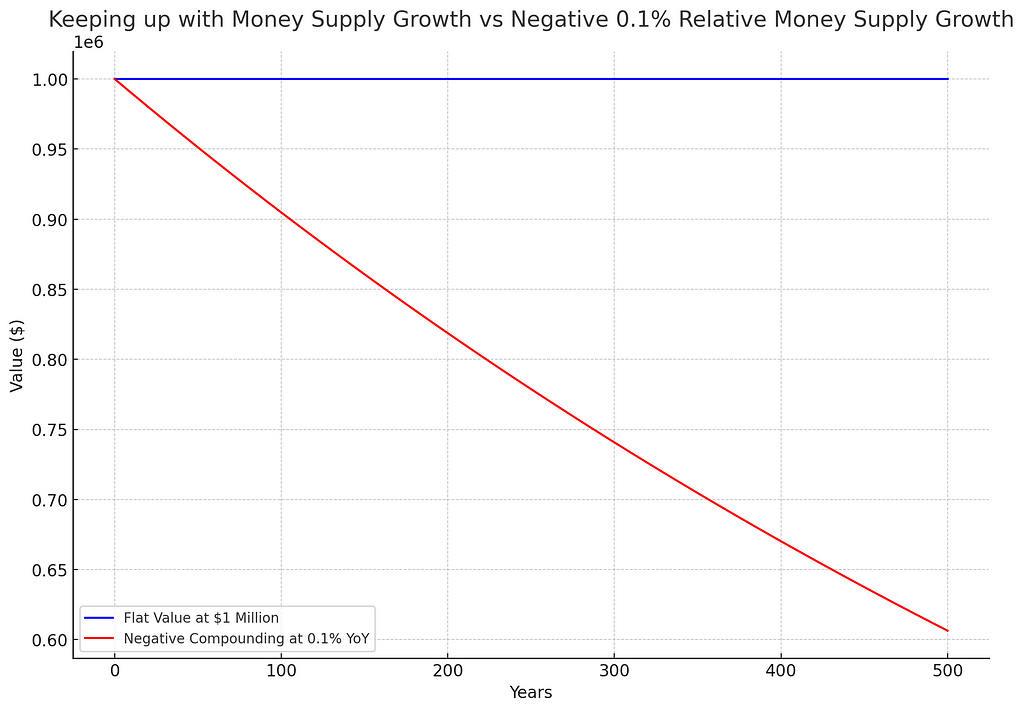

Another, perhaps more straightforward, way to grasp why true inflation aligns with the growth of the money supply is to consider an example involving an individual or a company that is nearly, but not quite, keeping pace with the rate of money expansion.

When demand persistently is set to outpace supply, scarcity is the unavoidable outcome, as no supply will ever be enough.Suppose the money supply is growing at an annual rate of 7%, while the individual or company’s capital increases by only 6.9%. This seemingly insignificant difference results in a negative growth of 0.1% relative to the monetary base. Over time, even this slight shortfall will cause the participant’s holdings to gradually shrink in proportion to the expanding monetary base, eventually becoming a minuscule fraction of the whole.

In an environment where demand — fuelled by monetary expansion — is consistently kept at a level that exceeds supply, even if it’s only “moderate,” every resource will inevitably become scarce. This comparison focuses on goods that are inherently scarce and desirable rather than those whose supply can be easily increased. However, the key takeaway is that when demand persistently is set to outpace supply, scarcity is the unavoidable outcome, as no supply will ever be enough.

Artificially inflating demand is like drinking salt water to quench thirst: it may provide a temporary illusion of relief, but it ultimately exacerbates the problem. No matter how much you drink, it will only make you thirstier.

Why Inflation is a Vector and Not CPI was originally published in The Capital on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

2 months ago

45

2 months ago

45

English (US) ·

English (US) ·